On the trail of the Bauhaus in Cologne

If Adenauer and Mr and Mrs Gropius had reached an agreement in 1924, Cologne could well have been in the running to become the second home of the Bauhaus. Apparently the then Mayor of Cologne went to great efforts to bring the Bauhaus to Cologne after the balance of power changed in Thuringia following the state elections in the same year and the school’s budget was cut by 50 per cent. It’s well known that history took a different course, and Dessau became the second home of the Bauhaus. But a great deal happened in Cologne and elsewhere in Germany that paved the way for the Bauhaus.

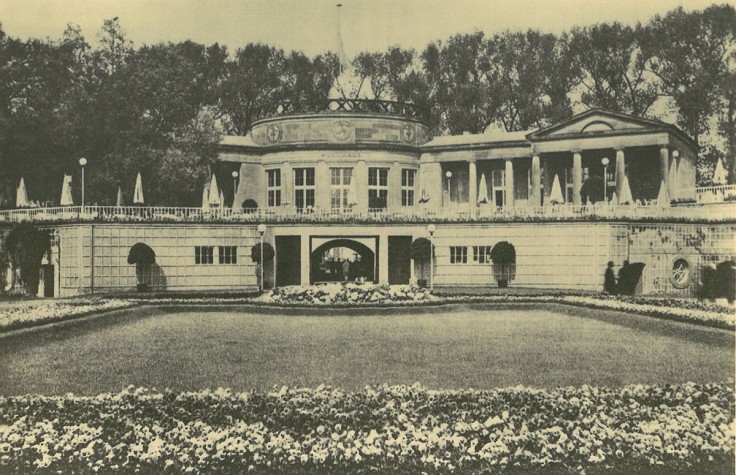

Building of the Werkbundausstellung 1914 in Cologne designed by Walter Gropius. Photo: Koelnmesse

The Deutscher Werkbund – a forerunner for the Bauhaus

The Deutscher Werkbund (German Work Federation, DWB) is considered one of the forerunners of the Bauhaus. It was the first association to form links between the crafts, art and industry. It was founded in Munich in 1907 by twelve architects and twelve entrepreneurs including Anna Teut, Lilly Reich, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Mia Seeger, Peter Behrens, Richard Riemerschmid, Theodor Heuss, Walter Gropius and Wilhelm Wagenfeld. The DWB aimed to increase the attractiveness of German products – from architecture to everyday items – on the global market. It may be hard to imagine it now, but back then, German products suffered from a rather poor reputation. The label “Made in Germany” was introduced in Great Britain in 1887 as a warning about cheap, inferior products.

The DWB also sought to counter the growing sense of alienation with a reformed, modern design of industrially manufactured products, architecture and living space in a sachlich or matter-of-fact style. The association wanted to bring together different fields of activity such as the design, production, sale and consumption of products by establishing values grounded in ethics such as quality, appropriate use of the material, functionality and sustainability. Last but not least, the DWB saw one of its core duties, alongside influencing the contemporary design of objects and ensembles, as promoting aesthetic education.

The 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne

The first Werkbund Exhibition, held in 1914 in Cologne, was one of the biggest exhibitions of the time, although it ended prematurely due to the First World War. The exhibition aimed to show an international audience what Germany was capable of producing. Henry van de Velde designed a theatre especially for the Werkbund Exhibition, while Walter Gropius designed a model factory, and Bruno Taut the famous Glass Pavilion. Intended to promote the glass industry, his expressionist glass dome took the shape of an asparagus tip. Taut designed the pavilion as a union of nature, art and technology. He sought to find a cosmic harmony with modern materials such as concrete, steel and glass.

During the exhibition, a debate on principles about the question of standardisation erupted between the architects and designers Henry van de Velde and Hermann Muthesius, who would become the second President of the DWB in 1916. While van de Velde advocated individual design of form, Muthesius argued for extensive standardisation as a means to improve quality. However, both sides in the debate placed equal importance on high standards for the artistic and functional quality of the artefacts and buildings produced.

Major cultural happening and a prestigious event

The Werkbund exhibition in Cologne opened its doors on 15 May 1914. Originally planned to run until October, it in fact lasted just three months due to the outbreak of the First World War. However, it attracted around one million visitors in this time. The audience took the opportunity to view 80 modern residential and industrial buildings on what is now the site of the Rheinterrassen and the Tanzbrunnen event venue, including the model village entitled New Lower Rhine Village and an amusement park. It was an exhibition of superlatives in which for the first time designers, craftspeople, artists, industrialists and architects enticed a wide section of the population with a new aesthetic that would have a formative influence on the creative sphere in the decades to come.

For the city of Cologne, this cultural event of the century was immensely important. It supported the exhibition in a wide variety of different ways: with staff, administration and five million Reichsmark – a budget five times greater than that of the Brussels world’s fair four years earlier. Notable backers and organisers such as the then Mayor of Cologne, Max Wallraf, and the Hagen entrepreneur and patron of the arts Karl Ernst Osthaus, who was the event’s main initiator, as well as Cologne’s Head of Building, Carl Rehorst, and the city’s Deputy Mayor, Konrad Adenauer, gave the exhibition their support and pushed ahead with work on its preparation.

The Bauhaus as a model for the Kölner Werkschulen

Now Mayor of Cologne for nine years, Konrad Adenauer renamed the long-standing School of Applied Arts (Kunstgewerbeschule) the Kölner Werkschulen (Cologne Art and Craft Schools) in 1926 and gave it a new orientation. He based these changes on the Bauhaus model, which united art and the crafts in a modern art school. The Kölner Werkschulen had their main buildings in Ubierring on the southern edge of Cologne’s city centre. The expressionist red-brick building – known as the “Rote Haus”, or red house – was designed by Martin Elsässer, at the time Chief Director of the Kunstgewerbeschule in Cologne. From then onwards, the Kölner Werkschulen taught architecture, sculpture and architectural sculpture, stage design, interior architecture, costume design, painting and the design of vestments and liturgical textile art, also known as paramentics. The school later introduced classes in free and applied graphic art, “photographics” and creative and technical design. The Cologne Institute for Religious Art was also incorporated.

The Kölner Werkschulen based their goals on the ideas of the Werkbund and promoted links between the schools and industry. Among the works produced by the schools that were commissioned by sporting associations and industry were the German Meisterschale (champions shield) and the German football trophy, the case for the Volksempfänger (an early radio receiver) and typefaces for typewriters. Werner Schriefers, who was director of the Kölner Werkschulen from 1965 to 1971, finally, with the takeover of the management of the Kölner Werkschulen, reinforced this orientation by integrating the industrial design department into the teaching programme, thus putting the focus in the education at the Kölner Werkschulen on the good design of industrial products.

Incorporation and end of the Kölner Werkschulen

In 1971, the Kölner Werkschulen were incorporated into the Cologne University of Applied Sciences as the Faculty of Art and Design. However, the faculty closed following a controversial reorganisation of the higher education landscape by the state government of North Rhine-Westphalia on 31 March 1993.

Among the tutors and students of the Kölner Werkschulen and what would become the faculty of the University of Applied Sciences were, in addition to the already mentioned, notable figures such as the architect Dominikus Böhm, the sculptor Hans Wissel, whose 6-metre-high allegorical sculpture from 1928 still adorns the old trade fair exhibition tower in Cologne-Deutz, the painters Jörg Immendorff and Daniel Spoerri and the architect Richard Riemerschmid. The schools’ famous students and graduates include the artists Rosemarie Trockel and Wolfgang Schulte, the sculptor Ulrich Rückriem, the photographers Chargesheimer, L. Fritz Gruber and Candida Höfer as well as Wolfgang Niedecken, the painter and frontman of the Cologne rock group BAP.

You might also be interested in:

Inside Thonet

Bauhaus Architecture in the Bergisches Land

100 years Bauhaus at the imm cologne

To the category "Design and Architecture"